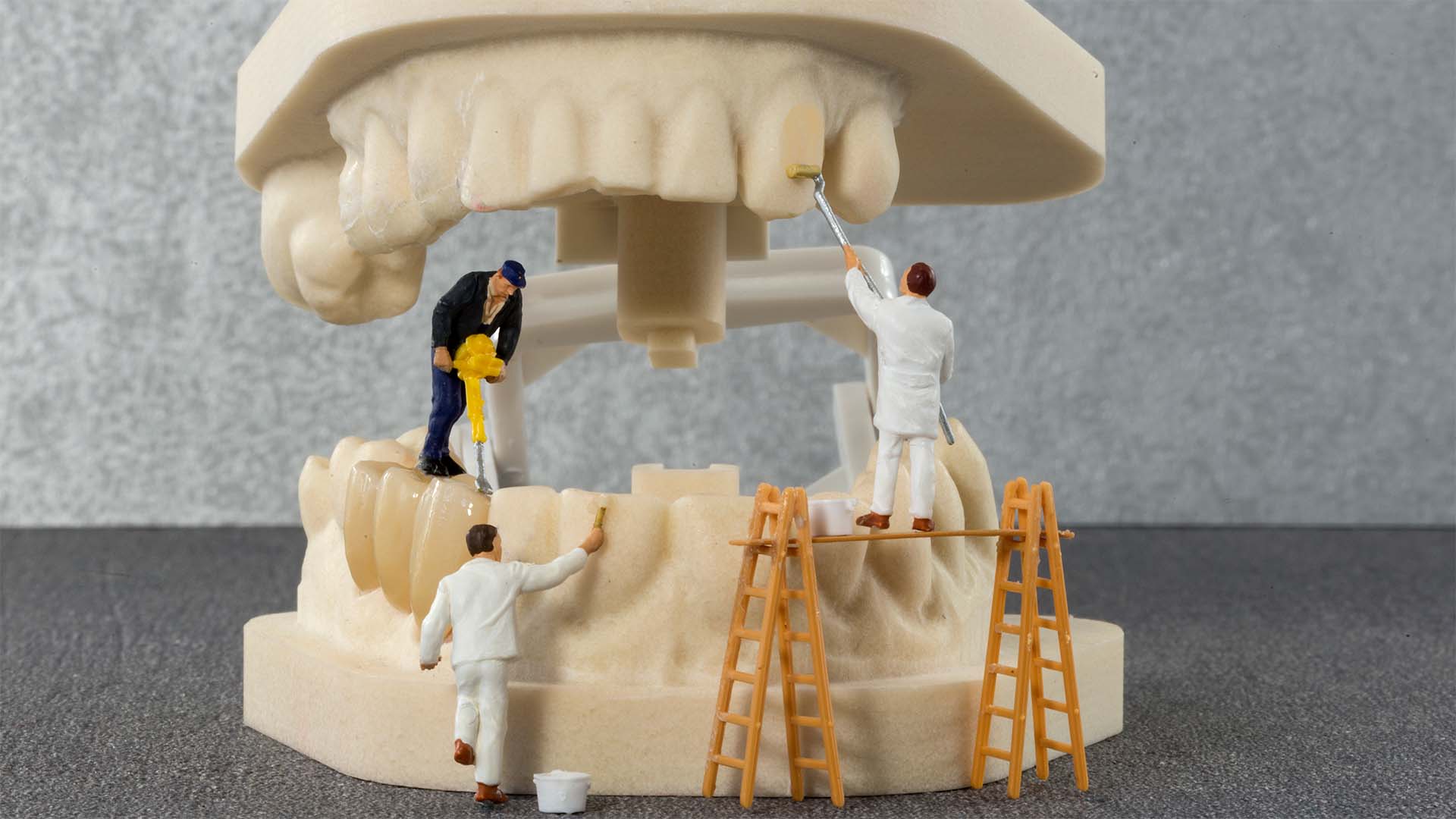

PRF/PRP in dentistry: real evidence or trend?

The promise sounds good: less pain, wounds that heal faster, implants that “take” better. PRP and PRF are concentrates of the patient’s own blood, rich in platelets and growth factors that act as a biological kickstart for tissue repair. The challenge is to separate what has been proven from what is still just enthusiasm. The purpose of this text is simple: to explain, in clear language, where the evidence is solid, where it remains unclear, and how to make informed decisions without giving in to fads.

PRF and PRP: how they work and how they differ

PRP is a liquid platelet concentrate prepared with anticoagulant. PRF forms a fibrin clot without anticoagulant that can be used as a membrane or fragmented. In practical terms, PRF releases growth factors more slowly and sustainably and provides a physical “scaffold” that protects the clot and soft tissues. PRP, being liquid, diffuses more easily and is used as an adjuvant in some grafting techniques. The choice is not black and white. It depends on the clinical objective, the preparation protocol, and the surgical technique. It is also important to recognize that different protocols and kits produce different concentrates, which explains some of the discrepancies between studies.

What the evidence confirms most consistently

Third molar extractions and other simple wisdom tooth surgeries are the domain where results are repeated: less pain in the first few days, less swelling, more favorable soft tissue healing, and fewer complications such as alveolitis in several studies. The effect size is small to moderate, but clinically significant. For those who need to return to work, study, or training, these days of comfort count. In implantology, using PRF as an adjuvant can slightly improve the secondary stability of the implant and the quality of the peri-implant soft tissues in the first weeks and months. It is not a dramatic leap, but it helps with comfort, marginal sealing, and hygiene around the implant, aspects that weigh heavily on the experience and inflammatory control.

Areas with mixed results and what still needs to be studied

In maxillary sinus elevation, adding PRF to the graft material appears to benefit some stability and comfort outcomes, but gains in new bone and bone height are not consistent across studies. In regenerative periodontics, combining PRF with established techniques may improve indicators such as clinical attachment level and bone filling in certain defects, although the effects vary and methodological heterogeneity remains high. In surgical endodontics, there are studies suggesting less pain and better radiographic healing with PRF, but the body of evidence is still limited and protocols are not well standardized. Honest summary: promising in several scenarios, definitive in few.

Security, logistics, and protocol variability

Because they are autologous, PRF and PRP have a favorable safety profile. The main risk is not in the product itself, but in its execution: sterile collection, adequate centrifugation, time between centrifugation and application, and correct contact with the surgical bed. Variability between kits, g-forces, and centrifugation times influences fibrin density, leukocyte count, and factor release over time. In logistical terms, there is cost, chair time, and the need for trained staff. It is therefore advisable to weigh the incremental benefit against the added complexity in each indication.

How to make an informed decision

Useful questions before proposing or accepting PRF/PRP: what is the most important outcome in this specific case—comfort in the early days, soft tissue healing, initial implant stability, measurable bone gain? Is there reasonable evidence for this outcome in that specific indication? Are there equivalent standard alternatives without increased complexity? Does the patient understand that this is an adjunct and not a substitute for technique, hygiene, and control of risk factors such as smoking or bruxism? With clear answers, the decision tends to be correct. In general, PRF makes more sense when we value postoperative comfort and soft tissue quality; its role in volumetric bone regeneration is, for now, complementary and dependent on the base technique.

Conclusion

PRF and PRP are not magic wands. They are biological tools with real utility when used judiciously: they modestly improve pain and initial healing after extractions, and can optimize soft tissue and early stability in implantology. In sinus lifts and periodontics, results exist, but they are less uniform and require careful selection. The balance lies in aligning expectations, choosing the outcome that matters to the patient, and using the adjuvant only when it measurably increases the likelihood of achieving that outcome. This is how science separates itself from hype.

References

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39003218/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39739059/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39318055/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39759623/

https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-025-05922-6

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11318657/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11451106/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38771493/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34923613/