When children’s sleep alerts through the mouth

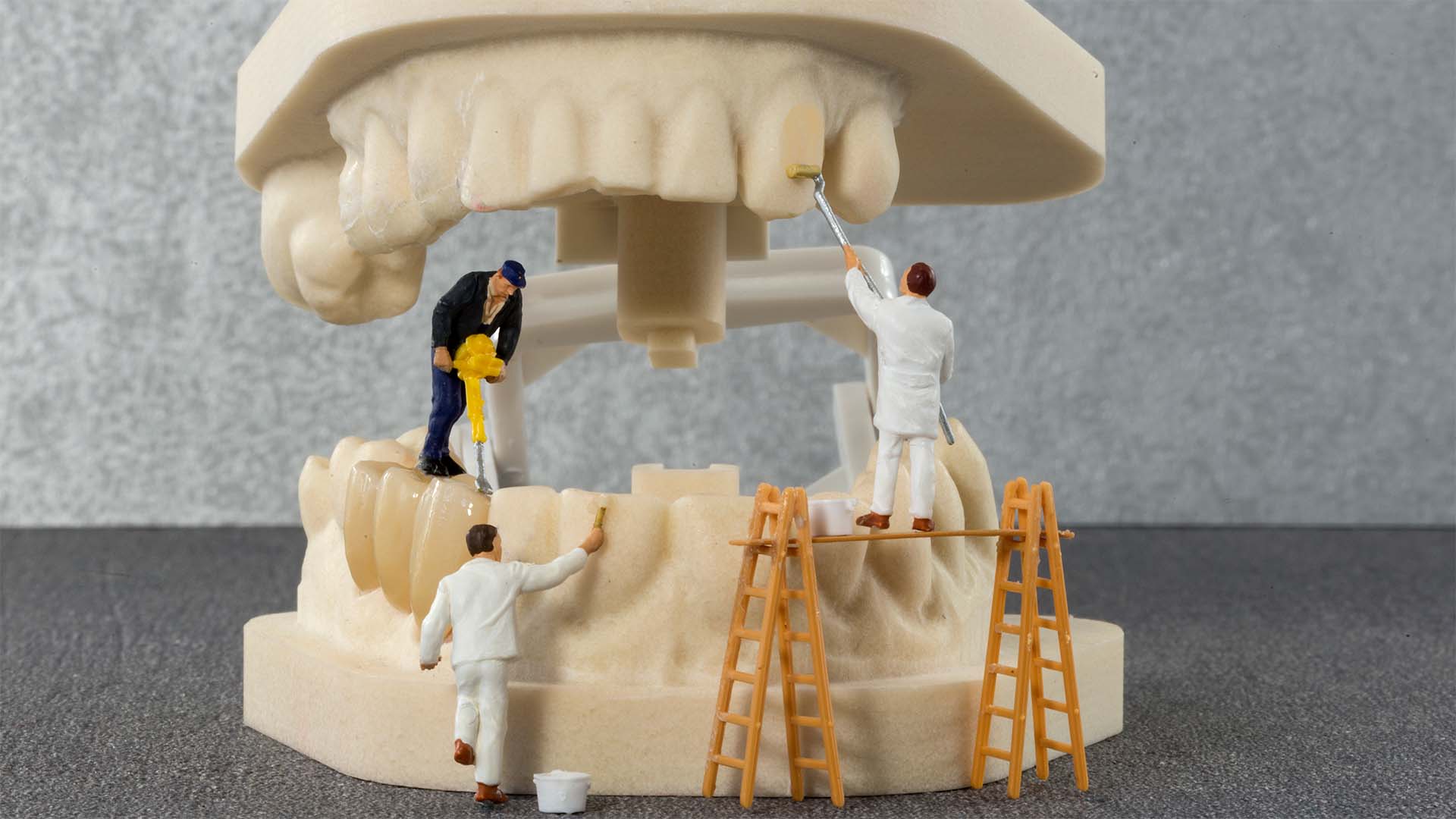

Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep-disordered breathing condition that affects approximately 1–5% of children, with peak incidence in preschool age (2–8 years). Unlike adults, signs and symptoms in children may be more subtle or atypical, contributing to a high rate of undiagnosed cases in childhood. Untreated pediatric OSA is associated with serious consequences for a child’s cognitive, behavioral, and physical development (e.g., learning difficulties, growth problems), reinforcing the importance of early diagnosis. Interestingly, many of the early signs of OSA in children manifest in the oral cavity and craniofacial structures, where dentists and orthodontists, who routinely evaluate pediatric patients, can identify “signs that start in the mouth” and refer the child for appropriate evaluation and treatment.

Oral and craniofacial signs associated with pediatric OSA

Several scientific studies have demonstrated correlations between pediatric OSA and oral or facial characteristics identifiable during dental examinations. Among the main signs and oral/craniofacial changes associated with sleep apnea in children are:

• Chronic mouth breathing – Children with nasopharyngeal obstruction (due, for example, to adenoid hypertrophy) tend to breathe through their mouth continuously, especially during sleep. This habit of persistent mouth breathing is linked to changes in facial growth and dental arch, as the lack of adequate nasal breathing can lead to anatomical adaptations that narrow the airways. The so-called “adenoid facies” (elongated face with mouth slightly open) is a classic phenotype of chronic mouth breathing in children with obstructed upper airways.

• Narrow maxilla and high palate – A transversely deficient maxillary arch with a vaulted palate is often observed in children with OSA. The high and narrow roof of the mouth is related to low tongue positioning (due to mouth breathing) and reduced nasal airflow, which are part of the set of craniofacial changes typical of pediatric OSA. Systematic review studies confirm that children with OSA tend to have narrower maxillae compared to children without OSA. Often, associated posterior crossbites are also found due to narrowing of the palate.

• Mandibular retrognathism and elongated face – Changes in mandibular growth and vertical facial growth patterns are associated with sleep apnea in childhood. Children with OSA often exhibit a more backward-positioned jaw (retrognathism) and an increased mandibular angle or lower facial height (more elongated face). This craniofacial configuration—often referred to as adenoid facies when combined with mouth breathing—contributes to airway narrowing. A recent meta-analysis reinforced that children with OSA tend to have a retruded mandible and increased vertical facial pattern, although the mean differences are small. In orthodontic terms, it is common to identify Class II malocclusion (disharmonious maxillomandibular relationship) in these patients.

• Increased overjet and open bite – Due to retrognathism or altered tongue positioning, children with OSA may have increased overjet (upper incisors protruding in front of the lower incisors) and even anterior open bite. Such malocclusions reflect muscular and growth imbalances associated with chronic mouth breathing and decreased muscle tone during sleep. The literature has pointed out that pronounced overjet and open bite occur more frequently in children with OSA compared to controls, although not all studies agree on the magnitude of this association.

• Tonsil and adenoid hypertrophy – Enlargement of the lymphoid tissue in the oropharynx (palatine tonsils) and nasopharynx (adenoids) is recognized as the most common anatomical risk factor for pediatric OSA. Dentists or physicians may visualize very large tonsils when examining a child’s oropharynx. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy leads to mechanical obstruction of the upper airway, resulting in snoring and apneas during sleep. In fact, enlarged tonsils/adenoids in children often cause mouth breathing and contribute to the craniofacial changes mentioned above. Surgical removal (adenotonsillectomy) is the first-line treatment in many cases of pediatric OSA, corroborating the central role of this anatomical cause.

• Sleep bruxism and other oral habits – There is evidence of a relationship between bruxism in children (grinding or clenching teeth during sleep) and OSA. Studies indicate that the prevalence of apnea is higher in children with bruxism than in those without the habit. In a study of Brazilian preschoolers, ~11% of children with bruxism also had obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, indicating a statistically significant association between the two conditions. Clinical reports also suggest that other oral parafunctions, such as thumb sucking, as well as temporomandibular joint pain upon waking, may occur more frequently in children with OSA. These findings reinforce the role of the dentist: bruxism and tooth wear in children should raise the alarm for investigation of possible sleep-disordered breathing.

Together, these characteristics constitute a typical—though not exclusive—craniofacial phenotype of children with sleep apnea. It is important to note that the presence of one or more of the above signs does not confirm a diagnosis of OSA, but indicates the need for further investigation. Dentists, when encountering these changes, can act as sentinels in the early identification of the problem.

Role of the dentist in early detection

Dental surgeons (including pediatric dentists and orthodontists) play a key role in the early identification of childhood sleep apnea. Because they evaluate children regularly (at six-monthly or annual preventive checkups), oral health professionals are in a privileged position to notice suspicious oral and craniofacial changes even before parents or pediatricians notice a problem.

According to guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), dentists should, during each routine clinical examination, look for signs that may raise suspicion of OSA in children. This includes: assessment of the size of the palatine tonsils (e.g., classifying oropharyngeal obstruction using the Mallampati index or Brodsky score), position of the tongue and palate (Friedman index), breathing pattern (oral or nasal), and dental occlusion. The medical history itself should include questions to parents about sleep symptoms, such as frequent loud snoring, observed breathing pauses, restless sleep, abnormal sleeping positions, daytime sleepiness, school difficulties, or even enuresis—all potential signs of sleep apnea in childhood. Screening tools, such as validated questionnaires (e.g., Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire – PSQ), can also be used by dentists to identify high-risk children.

When signs and symptoms suggest OSA, the dentist should refer the child to a specialist (usually an otolaryngologist or sleep doctor) for a complete diagnostic evaluation. A formal diagnosis of OSA requires a polysomnography (sleep study) conducted by a medical team. Thus, the dentist acts as a screening and referral agent, integrating into a multidisciplinary approach. In fact, the literature encourages the integration of dentists/orthodontists into the transdisciplinary pediatric sleep health team, given the contribution they can offer in screening and even in the adjunctive treatment of selected cases.

In addition to detection, dentists can contribute to the management of oral factors that aggravate OSA. For example, in children with very narrow maxillae and crossbites, rapid maxillary expansion (RME) performed by an orthodontist can widen the space in the arch and nasal cavity, improving airflow. Intraoral functional mandibular advancement devices (similar to those used in adults with OSA) have also been proposed for children with retrognathism, aiming to increase pharyngeal space during sleep. However, it is important to note that scientific evidence is still limited regarding the isolated effectiveness of these dental interventions in completely resolving childhood sleep apnea. The improvements observed tend to be partial and must be monitored over the long term. Thus, the main treatment for pediatric OSA remains under medical responsibility, with measures such as adenotonsillectomy, positional therapy, use of positive pressure (CPAP), or allergy management, with the dentist supporting the orofacial aspects and monitoring the development of the growing child’s airways.

In short, dentists are crucial allies in the fight against childhood OSA: by recognizing the “signs that start in the mouth” early on, they can catalyze timely diagnosis and intervention, preventing future complications.

Consequences of delayed diagnosis of childhood OSA

Early detection and proper treatment of sleep apnea in children is vital to avoid a number of negative consequences. If OSA goes unnoticed for a long time or remains untreated, the child may suffer various impacts on their health and quality of life, including:

• Neurocognitive and behavioral deficits: Chronic deprivation of quality sleep affects the developing child’s brain. Children with untreated OSA often exhibit hyperactivity, attention deficit, irritability, and poor school performance, symptoms that can be mistakenly attributed to attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or other disorders. Behavioral problems, aggression, and learning difficulties are reported as common in these patients. In cases of severe OSA, studies show reduced IQ and executive functions, as well as excessive daytime sleepiness that impairs concentration. In other words, untreated sleep apnea can significantly compromise a child’s neuropsychological development.

• Growth delay and failure to thrive: Deep, continuous sleep is essential for the release of growth hormone (GH) and other anabolic processes. Children with severe OSA often experience below-average physical growth and even failure to thrive, due to fragmented sleep and increased energy expenditure during apneas. Growth hormone may be suppressed due to frequent micro-awakenings and intermittent hypoxia. With proper treatment of OSA (e.g., removal of tonsils/adenoids), improvement in weight gain and height is often observed, indicating that the condition was interfering with the child’s normal development.

• Nocturnal enuresis: Bedwetting at night is a symptom reported in children with sleep apnea. Nocturnal enuresis is significantly associated with sleep-disordered breathing, possibly linked to nocturnal hormonal imbalances and unnoticed awakenings. When OSA is treated, episodes of enuresis tend to decrease, suggesting that fragmented sleep and respiratory effort contributed to the involuntary loss of urine.

• Long-term cardiovascular and metabolic problems: OSA is not just a sleep disorder—its systemic effects can follow the child into adulthood. Children with persistently untreated sleep apnea are at increased risk of developing high blood pressure, insulin resistance, obesity, and early cardiovascular disease. Follow-up studies indicate that many children with OSA continue to have sleep-disordered breathing in adolescence and adulthood, especially if risk factors such as obesity coexist. As a result, these young individuals are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome at an earlier age. In essence, failure to treat childhood OSA may mean incubating future adults with sleep apnea and its associated complications.

• Anesthetic and perioperative complications: A little-recognized danger of delayed diagnosis is that a child with unidentified OSA faces increased risk in situations involving sedation or general anesthesia. Due to their propensity for airway obstruction, such children may suffer serious respiratory events during medical procedures—there are reports of respiratory arrest and significant desaturation in pediatric patients with undiagnosed OSA undergoing anesthesia. Therefore, knowing the diagnosis of OSA in advance allows for extra precautions to be taken during surgery and for respiratory depressant medications to be avoided when possible.

• Severe neurological deficits (in extreme cases): Although rare, medical literature reports that severe and prolonged pediatric OSA, if left untreated, can lead to serious neurological complications, such as brain damage from repeated hypoxia, seizures, and even coma. These scenarios typically occur in extreme cases or in children with comorbidities, but they illustrate the spectrum of severity that the sleep disorder can reach if ignored.

• Effects on oral health: Indirectly, sleep apnea also affects children’s oral health. Disturbed sleep and mouth breathing are linked to a higher incidence of tooth decay and gum inflammation due to dry mouth and changes in salivation during the night. In addition, bruxism secondary to OSA causes tooth enamel wear and can lead to pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and facial muscles. Thus, dental problems such as tooth attrition and malocclusion can be both signs of OSA and consequences aggravated by its persistence.

In conclusion, a delayed or missed diagnosis of childhood sleep apnea can have far-reaching repercussions, ranging from behavioral and school problems to impaired physical growth and serious medical risks in the future. Therefore, there is a need for increased vigilance on the part of healthcare professionals—especially dentists, pediatricians, and otolaryngologists—to work together in the early detection and intervention of pediatric OSA. Identifying the “signs that start in the mouth” in a timely manner can prevent years of silent suffering for the child and provide for healthier and fuller development.